Kerry James Marshall Comes to London

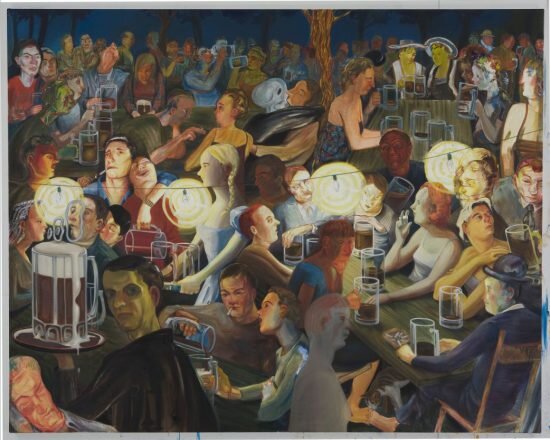

A fantastic show at the Royal Academy in London of the work of American artist Kerry James Marshall. He’s an artist who never stops bewitching us with art which confronts the absence of Black subjects in Western art history; complicated, at times mischievous works, which are both critically rich and visually stunning. It was so good to see School of Beauty, School of Culture, one of his paintings of modern life in which he re-works arrangements and elements from famous paintings, in this case Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors, where he transforms the anamorphic skull into a distorted Disney Sleeping Beauty, disturbing the space of a beauty salon.

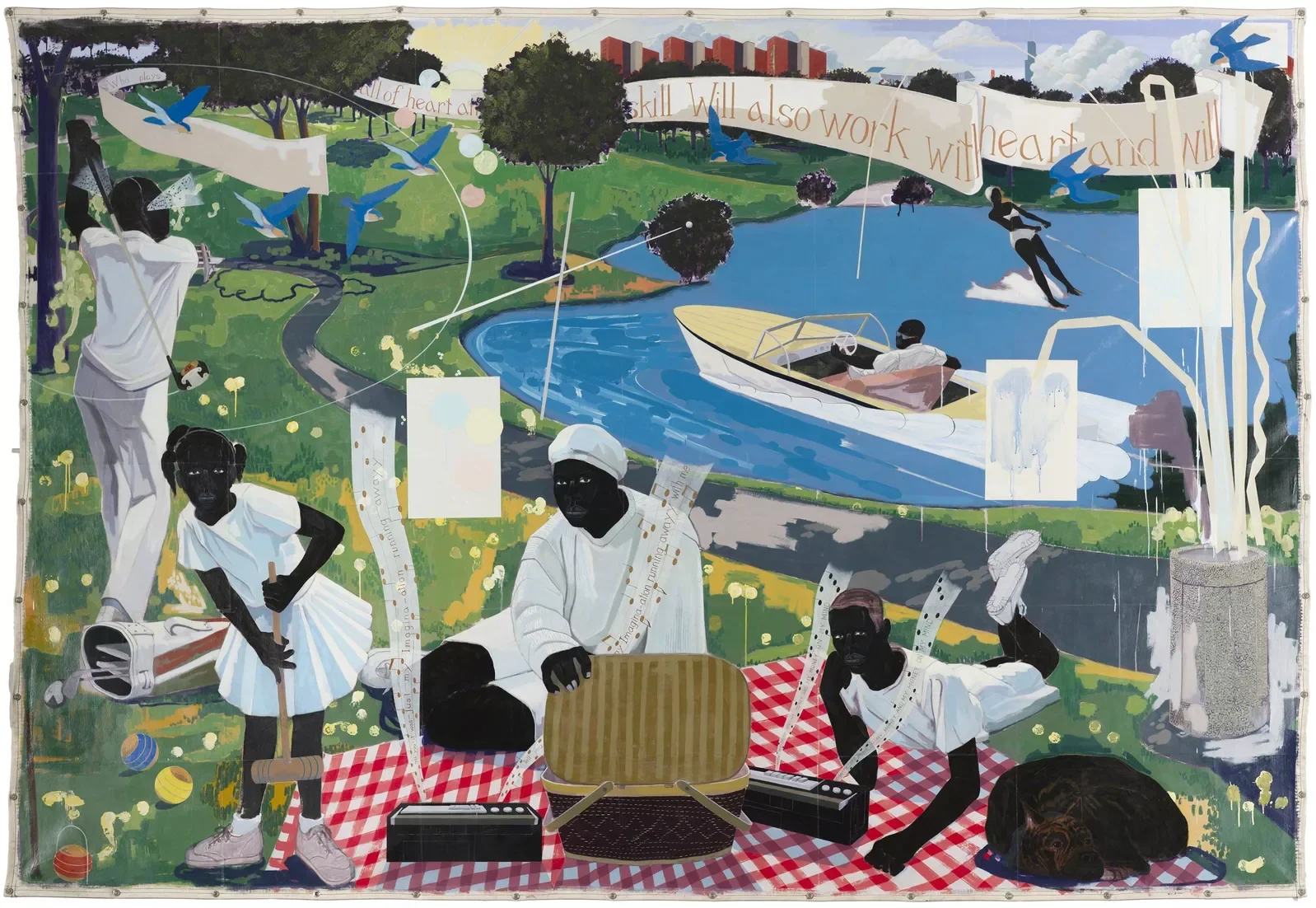

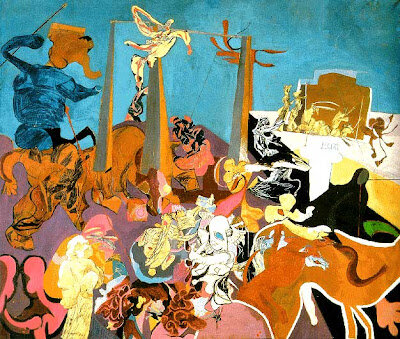

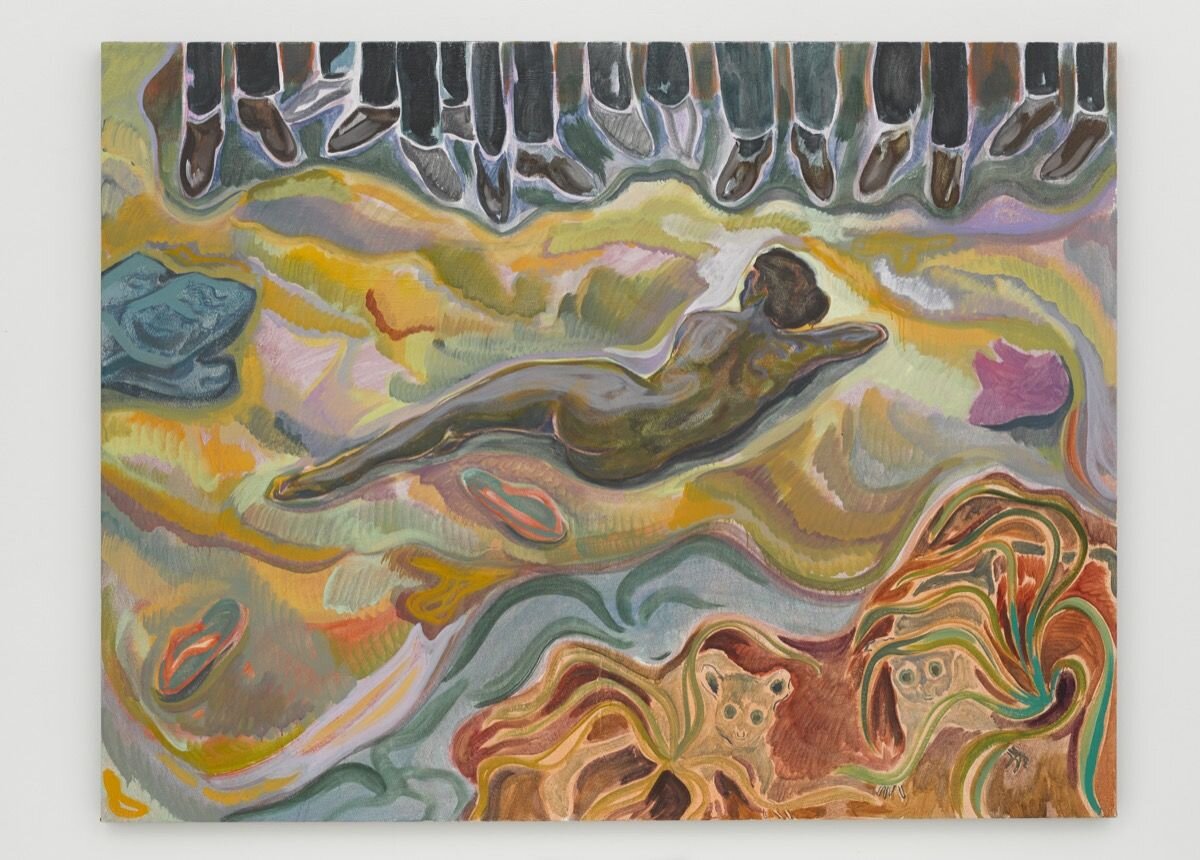

Kerry James Marshall, Past Times

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnieres, 1884

Marshall uses tropes,styles and subjects associated and grounded within the Western artistic traditions to highlight the historical exclusions in artistic narrative. As you walk round the show, you find yourself asking ‘What if?’. What if Seurat’s bathers were black? Running through all Marshall’s work is flesh of intense black-not shades of brown-but BLACK.

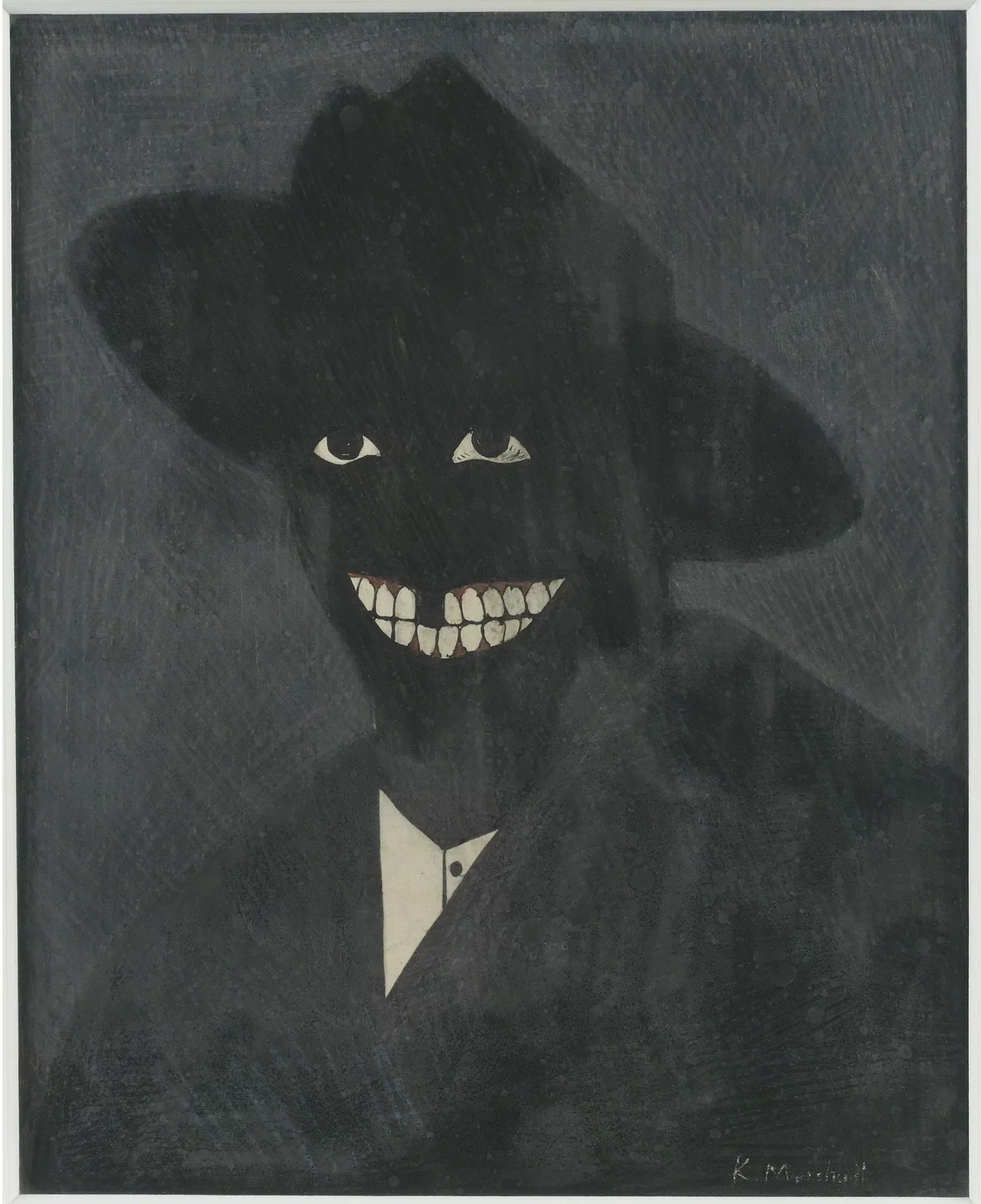

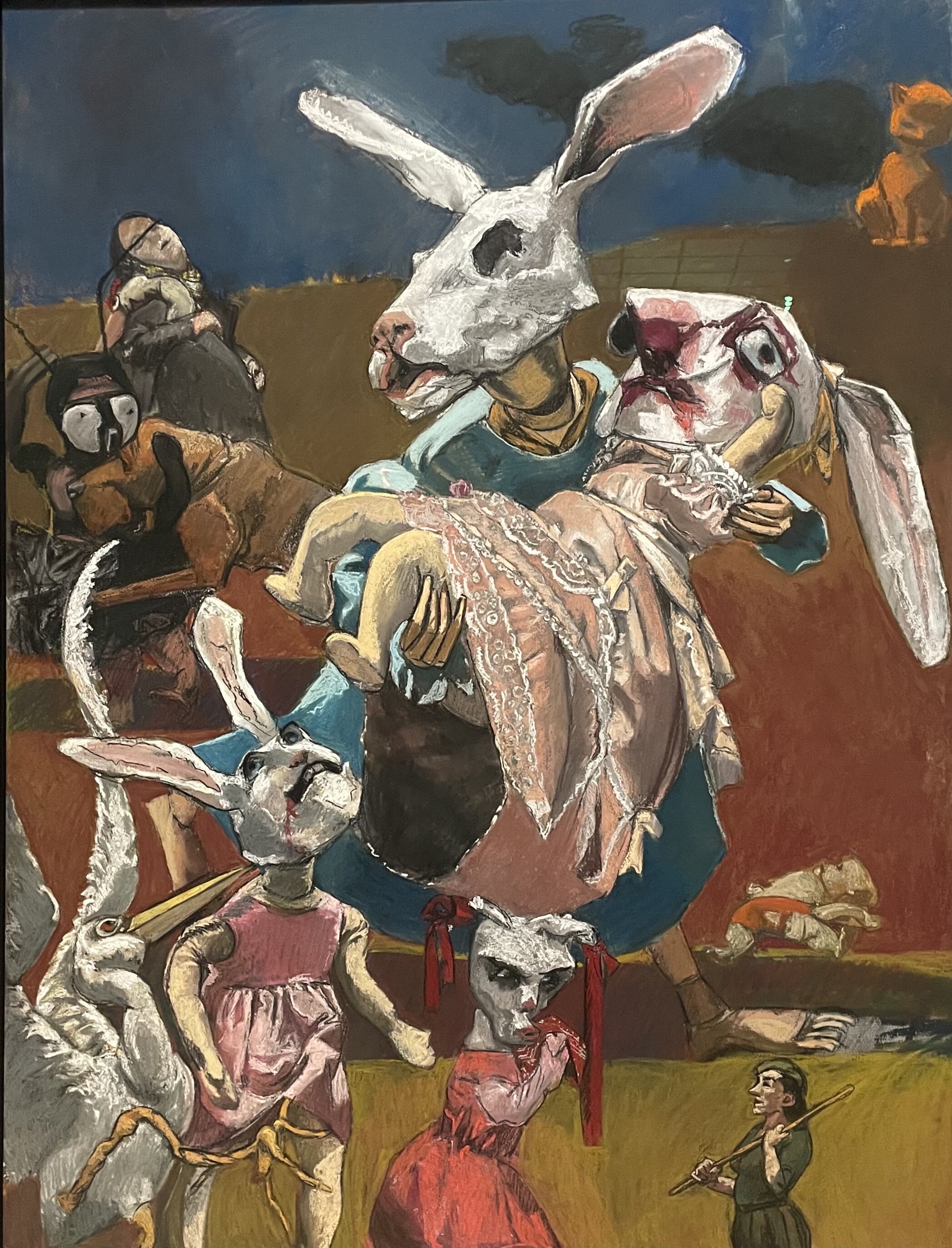

Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self,1980

In Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, Marshall features a man whose jet black skin can just barely be distinguished from the dark gray background. His teeth and eyeballs disrupt the surface with shocks of white. It’s a disturbing work which echoes Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and the bizarre and insulting Black and White Minstrel Show which appeared on the BBC from 1958-1978. And of course that’s the point. This blackness, near on 'invisible, reflects a centuries long history of representations of blackness as either evil, comical, inferior or simply absent. Marshall’s portraits and genre scenes-his painting of modern life, have such force and profundity precisely because they disrupt the historical canon which they embrace. In his works, Black lives truly matter.