John Singer Sargent: A Dedicated Follower of Fashion

After three weeks of work on this portrait, John Singer Sargent described himself as a painter and a dressmaker. Lady Helen originally posed in a white dress; that was not quite the right look for Sargent. So he created a new garment in black. It shows you the lengths he would go to make sure that the sitter’s clothing-what it was made of, how it hung-was just right for his meticulously curated look. Sargent was the designer, draping fabric around her; a creative director, a stylist in today’s context. His brushstrokes were like a tailor’s pins, darts and folds. By comparing himself to a dressmaker he reaffirmed the centrality of fashion to his art. Sargent painted this portrait of Lady Helen Vincent in Venice. You can just see what was Grand Canal, visible through the balustrade in the lower-left corner. Long arms and neck, emphasising her gracefulness, while the black fabric -a hint of fur trim at the bustline-highlights her milk-white skin, traditionally a sign of her nobility. As with 18th century grand manner portraits, her direct, but pensive gaze, suggests her intellect: she was a member of The Souls, a salon of prominent intellectuals that included Sargent's friends, the writers Henry James and Edith Wharton. So, here’s this fashionable, turn of the century IT girl-portrayed by the most sought after stylist of the day- that would be a winning combo for any 21st century influencer!

Lady Sassoon, (Aline de Rothschild),1907

Just look at the energy of this 1907 portrait of Sargent’s friend Lady Sassoon. She’s shown wearing a sweeping black opera cloak; it has been pinned and folded by Sargent in such a way as to expose the salmon pink lining- accents of colour which appear so spontaneous yet are carefully constructed by the master stylist. All that movement, you can almost hear the rustle of the crisp silk taffeta. Sargent was an artist who loved fabric and loved painting it.

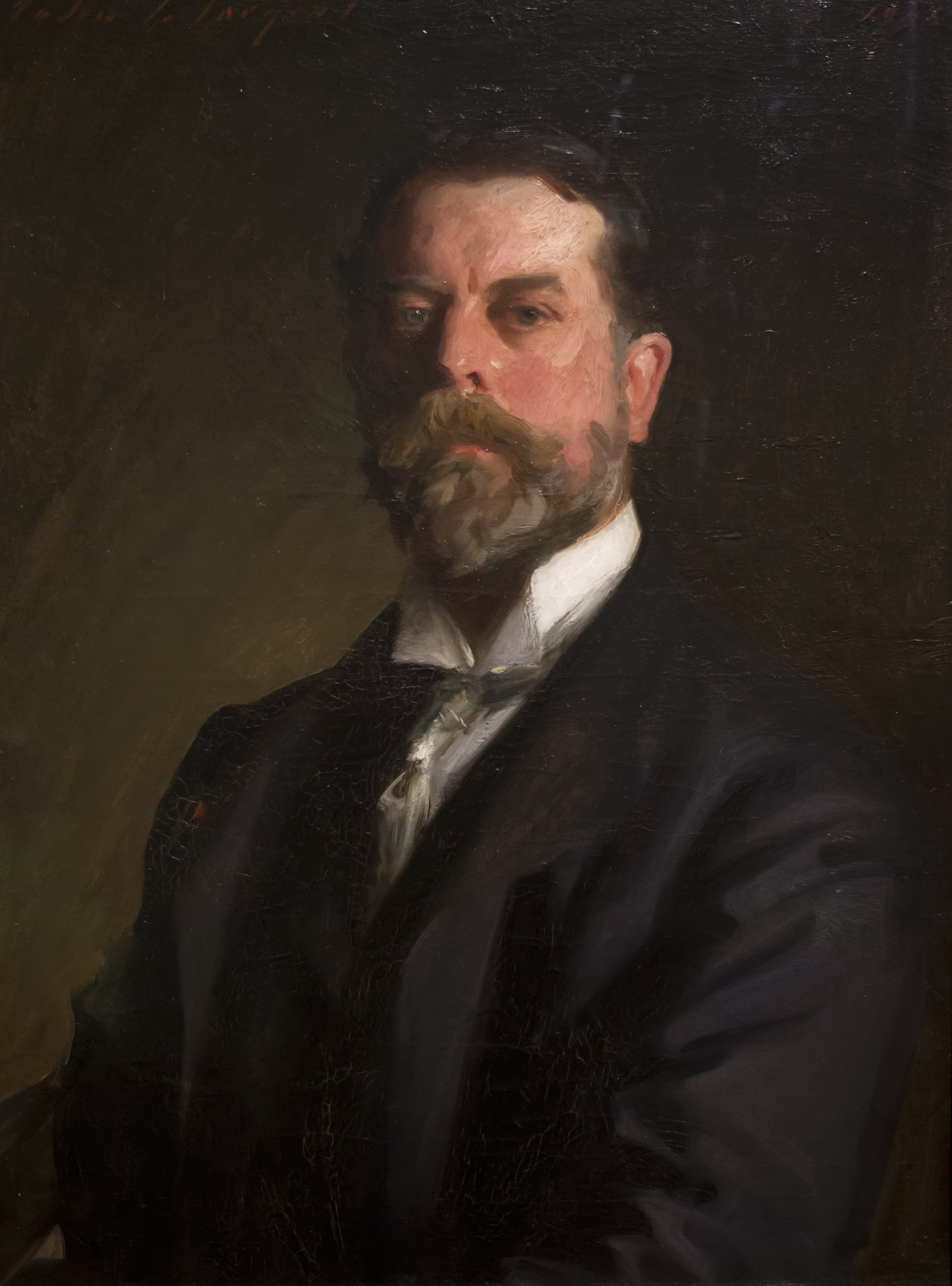

John Singer Sargent,Self Portrait, 1906

Sargent was the consummate portrait painter to the rich and famous in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His international clientele included wealthy aristocrats, industrialists, presidents, politicians as well as nouveau riche society types, bohemian writers, artists and performers. A portrait by Sargent was your golden ticket to society. Born in Florence in 1856, his parents were ex-pat Americans who’d come to Europe in search of culture. In the words of one biographer: ‘they went to Europe and forgot to go home’. His father had been a promising Philadelphia surgeon, Mrs Sargent had a small family inheritance to help them along. They loved travel and like many Americans abroad at this time.they lived quite a bohemian lifestyle, flitting between Florence,Paris, Nice and the Alps, rootless but stimulating. This itinerant expat life made Sargent very ambitious to succeed.

He did not set foot in America until his was 21, arriving for the first time in 1876 (his family thought it was about time the children met their American relations). He was cosmopolitan-mid-Atlantic: European- American?American-European? British? All of it. He spoke Italian, French, German and English, although he always considered himself to be an American, or as he once wrote to his friend and fellow artist James MacNeil Whistler: ‘I keep my twang’. Above all he was Sargent, hovering over the the Paris Salon, the Royal Academy, and leading American art associations, tailoring his work to suit national tastes of his sitters. When he died in 1925 French, British and American art critics all claimed a part of him...

How fitting that this portrait should be in his birthplace- the famous collection of artists’ self-portraits housed in the Vasari Corridor in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence; portraits going back to Renaissance times. Many of the great names in European art are represented there and Sargent was one of the first Americans to be invited to contribute a self-portrait. He presents himself in formal attire proudly wearing his Légion d’Honneur pin (represented by a small red dab on his right lapel )-France’s highest honour and a mark of his international success.

Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, 1892

Sargent was as adept at manipulating fashion as he was in handling his long paint- loaded brushes. He had leaned his technique from the French artist Charles Emile Auguste Durand-known as Carolus Durand. When Sargent enetered his studio in 1874,he quickly became his star pupil. Durand’s approach was radical for the time. He encouraged his students to draw straight from the brush-au premier coup- at first stroke. It was a technique in which new paint was applied over existing layers of paint while still wet. It was from this time that Sargent developed such remarkable self-assurance in handling paint.

Portraits like this were as much about the dress as they were about the sitter. For Sargent there was an entire culture behind dress-the costume. This is the time of haute couture- famous names like The House of Worth and Jeanne Paquin- and dresses like these were what the writer and friend of Sargent’s, Edith Wharton described as one’s ' social armour-the defence against the unknown and a your defiance of it'.

At the height of his career Sargent charged 1000 guineas for a full length portrait or £500 for a three quarter; that’s about £120,000 in today’s money. Gowns like this one probably cost between £20,000 to £30,000 in today’s money.

Not everyone liked Sargent’s work: Walter Sickert dismissed it as the ‘chiffon and wriggle of social portraiture’. D.H. Lawrence said ‘ Sargent’s portraits were nothing more than yards and yards of satin from the most expensive shops- having some pretty head propped up on top’

This particular pretty head was Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, painted in 1892, (now at the National Gallery of Scotland). It was this work that firmly established Sargent’s reputation in Britain. A celebrated dark haired beauty-Gertrude Vernon- she was in poor health at the time and so this was painted in just 6 sittings.

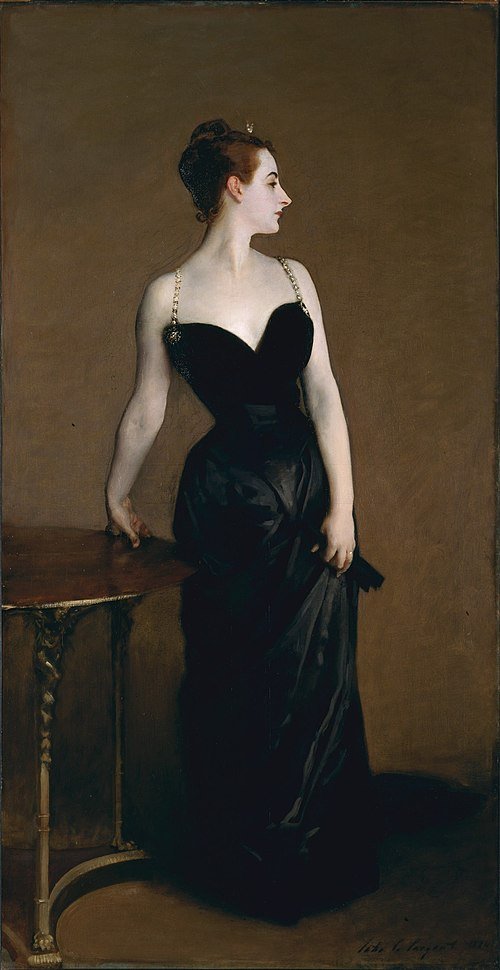

Madame X, 1883-84

Sargent is of course best known for this portrait, Mme X. If ever there was a dress and a portrait which caused a stir it was this one. Mme X , Virginie Gautreau- (nee Avegno) , an American from New Orleans who moved to Paris in 1867 after her father died during the Civil War. She married a Paris banker and shipping magnate; she was known as a professional beauty. Every artist wanted to paint her and Sargent became obsessed with her after they met in 1882: ‘I have a great desire to paint her portrait , and have reason to think she would allow it and is waiting for someone to propose this homage to her beauty' he wrote, ‘you might tell her I am a man of prodigious talent'. He finally convinced her to let him paint her. She probably didn't need that much convincing: a portrait by Sargent would fit in to her meticulous strategy of self-promotion. She’s portrayed in almost Mannerist style, as a quintessential nouvelle femme Parisienne-just as she intended-sophisticated, perfectly groomed, elegantly dressed, modern and independent.

Sargent originally painted the right shoulder strap sliding off her shoulder as shown in the Tate’s study below, but this was too much for the critics and after the Salon show he re-painted the strap.

Both these provocative depictions underscored a sense of 'foreign otherness' for the critics--the fallen shoulder strap exemplified poor taste from BOTH sitter and the artist-a mistake that no true Parisienne or Frenchman, would have made. So the portrait became a symbol of BOTH artist and sitter who, according to French critics, were upstart Americans who threatened to topple long standing hierarchies in fashion, society and national identity. The colour black was as important to Sargent as white. During the 1880s he painted almost half his female sitters in black; the colour was so important to him that when he visited his friend Claude Monet he was unable to paint because Monet had no black pigment!

Mme X, study, 1883-4

Sargent died in his sleep in 1925 age 69. His reputation went into freefall after his death. Sargent’s great nephew, the art historian Richard Ormond, blames this mainly on the antagonism of his former friend, the influential critic Roger Fry, who came to see Sargent as irrelevant to 20th-century modernism-understandable perhaps in the context of the time, however I think his society portraits are as relevant today as they were then. Sargent has a central role in the social function of portraiture: the way it can manufacture identity -superficially AND existentially. Sargent was a dedicated PORTRAYER of fashion, a dedicated FOLLOWER of the fashionable, and an artist who made fashion and identity central and defining elements of his painting.