A Breath of Fresh Paint: A Revival of Figurative Art and the Changing Face of Portraiture

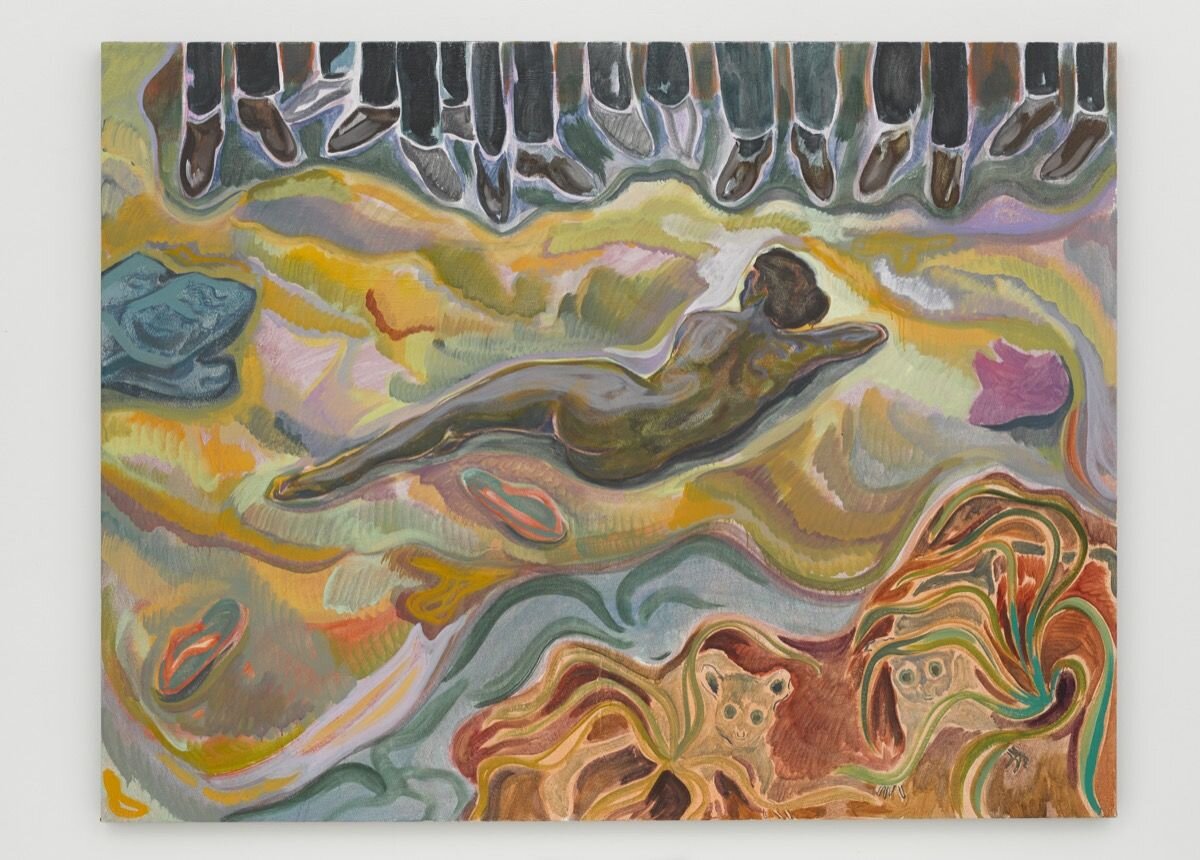

#mydressmychoice” (2015) by Michael Armitage (© Michael Armitage, photo © White Cube/George Darrell)

Who says painting is dead? The curators of a new show at London’s Whitechapel Gallery would have us believe that painting had its last hurrah in the 1980s. The stock market boom, powered by the wolves of Wall Street and Square Mile wide- boys, was bankrolling the neo-expressionist swagger of artists like Julian Schnabel, Georg Baselitz and Philip Guston. That “hurrah” was best exemplified by the seminal show at the Royal Academy in 1981, A New Spirit of Painting, which featured 38 artists—all, incidentally, white men—who broke free from the chains of minimalism and abstraction to champion figurative art.

Since then, according to the Whitechapel curators, representational painting has lost its appeal, is past its sell-by date, and has been largely overtaken by photography and video produced by ambitious young artists. In a century dominated by digital photography (a jaw-dropping 1.8 billion images are uploaded every day) how can painting ever compete?

For your answer, walk around Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium. Instagram selfies are so last year: this is a show articulating topical social issues with new energy, showing how the paintbrush is so much more powerful than the camera in its capacity to portray an inner psychological world, of the self, the body, race and gender. Reports of the death of figurative painting have been greatly exaggerated. Chris Ofili, Peter Doig, or Luc Tuymans, to name but a few established figurative painters, are not exactly languishing in obscurity, despite the ubiquitousness of the photography or conceptual art installations that continue to bemuse most gallery visitors.

Curatorial headline-grabbing aside, Radical Figures deserves attention. The Whitechapel’s director, Iwona Blazwick, says it highlights 10 of the “most exciting artists working in figurative painting today”. In stark contrast with the 1981 Royal Academy show, seven of the painters are women and four are artists of colour. The choice is inevitably subjective: who is to say there would not be 10 completely different “exciting” artists chosen at another venue? Well, the more the merrier. This is a truly enthralling vibrant display of young talent.

“Tarifa” (2001) by Daniel Richter (courtesy of Galerie Thaddeus Ropac, London)

The dialogue with art history is genuine. Tarifa (2001), by the German Daniel Richter, evokes the notion of the sublime and the terror of dramas at sea, referencing Theodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa and Turner’s The Shipwreck. Painted at the time when night vision technology started to be used by the military and the police, it is a harrowing and alarmingly prescient image showing a small inflatable raft tossed in a dark sea, overloaded with refugees huddling in fear.

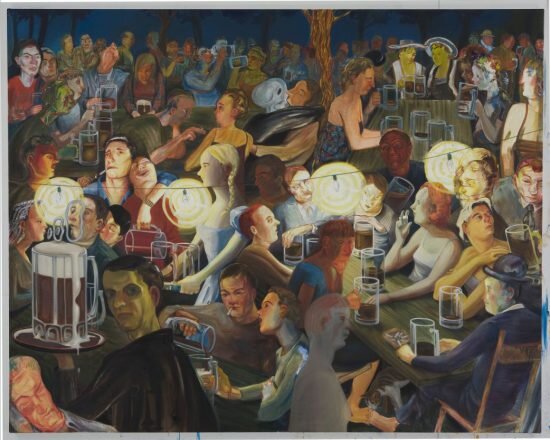

Nicole Eisenman’s Brooklyn Biergarten II (2008)

Nicole Eisenman’s Brooklyn Biergarten II (2008), painted at the height of the 2008 crash, shows artists, hipsters and businessmen drowning their sorrows, echoing Édouard Manet’s masterpiece of Parisian bourgeois entertainment, Music in the Tuileries (1862); her Progress, Real and Imagined (2006), below, meanwhile, has clear references to Pieter Bruegel and Hieronymus Bosch.

But painters have always engaged in visual conversations with their predecessors. Turner was, after all, known as the “British Claude”.

Right panel of “Progress, Real and Imagined” (2006) by Nicole Eisenman (courtesy of Ringier AG/Sammlung Ringier, Switzerland)

Kenyan-born Michael Armitage uses social media videos as a source for his subjects. #mydressmychoice (2015) - see above-is taken from an incident in 2014 in which a woman was assaulted and stripped by a group of men while waiting for a bus in Nairobi. The attackers accused the victim, who wore a miniskirt, of “tempting” them with “indecent” clothing. The attack was captured on a video that was posted on YouTube and went viral. Thousands took to the streets in uproar, under the hashtag #MyDressMyChoice.

In this work, the pose of the woman is a direct reference to Diego Velàzquez’s Rokeby Venus, the mirror replaced by the “male gaze” of the attackers’ shoes. Armitage tells me that the fascination lies in the conflation of beauty with something truly horrible and violent. “Painting is still and silent, so it gives us more time to reflect on the full horrors of what this scene depicts”. Precisely because it consists of recognisable images articulated through paint, figurative work, Armitage claims, unlike abstraction or conceptual art, is a far more powerful way of engaging and reflecting life.

This reinvigoration of figurative painting has been especially championed among black artists, such as the British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s enigmatic portraits of imagined black subjects (a retrospective of her work was scheduled to be at Tate Britain from May 20 to August 31; the Tate galleries are now closed until at least June 1), and the Chicago-based Kerry James Marshall. In both cases it is figurative painting that lends greater potency to the representation of issues of identity and racial stereotyping.

Kehinde Wiley is a young African-American painter who is quite literally changing the faces of portraiture with his pulsating and political depictions of black men and women, ranging from young people he meets on the street (a process he calls “streetcasting”) to rap artists, and even Barack Obama, whose 2018 portrait now hangs in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC. Wiley has made his name with hyper-realistic, brightly coloured portraits, often with dramatic botanical backdrops. He challenges viewers’ preconceptions of people of colour and brings them into museums and galleries where they have, up to now, been largely excluded. His works are represented in every major museum in the United States.

His portraits give power to those without it, turning the privileged and elitist identity of traditional portraiture— the “field of power”—on its head.

Installation view of “Portrait of Melissa Thompson” by Kehinde Wiley. (© Kehinde Wiley, 2020. Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Photography by Nicola Tree)

Wiley’s latest venture is a collaboration with the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow in London. Long inspired by the floral motifs of William Morris, he first came to know the designs while helping his mother sell bric-à-brac in South Central Los Angeles in the 1980s. In what must surely be a coup for the gallery, this is his first solo exhibition at a public institution in the UK. It is also the first time he features portraits exclusively of women, all of whom he met last summer in Dalston. Kehinde Wiley: The Yellow Wallpaper takes its name from the 1892 text “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. The short story, much loved by literary theorists, is a semi-autobiographical and proto-feminist tale of a new mother confined to her bedroom after being diagnosed with “hysteria”. The room’s yellow wallpaper design takes on a monstrous life of its own, contributing to her paranoia. It is a consuming, psychological parable of the dangers of denying women their independence. In deliberate contrast, Wiley’s Dalston women break out of their yellow wallpaper like powerful warriors; they are palpably not objects of consumption for the male gaze or control.

Wiley’s work is right at home in a museum dedicated to Morris, the great socialist maverick who passionately believed that art and design could change people’s lives. These monumental East End women are immortalised in a Grand Manner style in an artform previously reserved for royalty, aristocratic landowners or simply the very rich and famous. Museums can no longer afford to ignore or exclude culturally the people who live their lives outside their doors. Wiley’s portraits address centuries of inequality and lack of representation with scintillating and empowering images that turn the genre on its head.

Installation view of “Portrait of Dorinda Essah” by Kehinde Wiley. (© Kehinde Wiley, 2020. Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Photography by Nicola Tree)

“Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium” is at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, and will run until August 30th. “Kehinde Wiley: The Yellow Wallpaper” was at the William Morris Gallery. The gallery is still shut due to Covid; please check website for reopening news

This article appeared in the March 2020 edition of Standpoint Magazine